Santa Monica Boulevard and Fifth Street

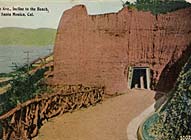

Oregon Avenue Incline to the Beach, Santa Monica, CA

Oregon Avenue Sidewalk Sign,

pre 1912

Sidewalk marker looking north

Example of the three balls

symbolizing a pawn shop

Santa Monica meat market, 1890 - SMPL

Northside, Williamsburg

Street sign chiseled on building side

Bet you have been dying for a brief history of street signs, courtesy of the National Park Service.

Pre-Nineteenth Century Signs

American sign practices originated largely in Europe. The earliest commercial

signs included symbols of the merchant's goods or tradesman's craft. Emblems

were mounted on poles, suspended from buildings, or painted on hanging

wooden boards. Symbols accompanied words in the days when most of society

could not read - a sheep signified a tailor, a tankard a tavern…

The red and white striped pole signifying the barbershop, and the three gold balls outside the pawnshop are two such emblems that can occasionally be seen today. (The barber's sign survives from an era when barbers were also surgeons; the emblem suggests bloody bandages associated with the craft. The pawnbroker's sign is a sign of a sign: it derives from the coat of arms of the Medici banking family.)

Flat signs with lettering mounted flush against the building gradually replaced hanging, symbolic signs. The suspended signs posed safety hazards, and creaked when they swayed in the wind: "The creaking signs not only kept the citizens awake at night, but they knocked them off their horses, and occasionally fell on them too." The result, in England, was a law in 1762 banning large projecting signs. In 1797 all projecting signs were forbidden, although some establishments, notably "public houses," retained the hanging sign tradition."(1)

By the end of the eighteenth century, the hanging sign had declined in popularity. Flat or flush-mounted signs, on the other hand, had become standard.

Nineteenth Century Signs and Sign Practices

Surviving nineteenth-century photographs depict a great variety of signs.

Fascia signs, placed on the fascia or horizontal band between the storefront

and the second floor, were among the most common. The fascia is often

called the "signboard", and as the word implies, provided a

perfect place for a sign--then as now. The narrowness of the fascia imposed

strict limits on the sign maker, however, and such signs usually gave

little more than the name of the business and perhaps a street number.

New York City used fascia signs as its street markers. In the 19th Century, and in the early years of the Twentieth, street names were commonly chiseled into the sides of buildings abutting the street they faced, or mounted on gas lamps. If you know where to look, you can find original street names on buildings that were constructed decades ago. For example, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a building on Bedford and South 4th Street has Fourth St and South Fourth Street chiseled on its side. Fourth and South Fourth St. intersected in the 1880s!

In parts of New England, where snow covered the ground much of the year, street names were carved into small posts. In the wild, wild west, names laid into the ground.

Sign information courtesy of the National Park Service Preservation Briefs

25: The Preservation of Historic Signs. http://www.cr.nps.gov/hps/tps/briefs/brief25.htm